Introduction

Mundane astrology is arguably one of the oldest and most ambitious branches of astrology. Since antiquity, astrologers have studied the heavens to read the upheavals of empires, the birth of civilizations, wars, and periods of renewal.

It does not concern itself with individual destinies, but with the movements of history, collective climates, and those times when the world seems to be entering a critical phase—or, on the contrary, to be reborn under a more favorable sky.

Far from common caricatures, mundane astrology is based on a methodological foundation: the study of long planetary cycles, major aspects, and transitional periods marked by planetary ingresses into new signs.

Among the most influential researchers in this field, André Barbault holds a central place. Throughout the 20th century, he analyzed the correlation between the cycles of the outer planets and the major turning points of world history. His famous “curve of planetary concentration,” though debated, remains a landmark in contemporary mundane astrology.

But the discipline is not without its gray areas. It faces the inherent difficulty of interpreting events whose causes are multiple and whose dates are not always clear. It must exercise extreme caution when studying event charts—or worse, when projecting planetary lines onto a world map to suggest zones of conflict or harmony, as astrocartography attempts to do, with a graphic appeal inversely proportional to its actual reliability.

This article offers a critical yet constructive overview of mundane astrology: what it can genuinely offer as a tool for historical and cyclical analysis—and where, in order to remain credible, it must be careful not to overreach.

The Great Celestial Clocks

Mundane astrology is fundamentally based on the observation of slow planetary cycles. It is the movements of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto that structure the great periods of history. Their slowness is precisely what makes them relevant for analyzing collective shifts: their influence does not concern individuals, but entire generations.

Among the most studied cycles is that of Jupiter–Saturn, which lasts about 20 years on average. It often marks major political and economic turning points. Charles Harvey explored its ideological implications. On a broader scale, the Saturn–Pluto and Uranus–Pluto conjunctions are frequently associated with deep crises, radical reforms, or the collapse of established orders.

Richard Tarnas continued this line of inquiry, showing how certain planetary configurations—especially squares and conjunctions between outer planets—coincide with major periods of historical upheaval: wars, revolutions, cultural transformations. It is not about direct causality, but symbolic resonance, a climate of archetypes.

Lastly, planetary ingresses—the entrance of planets into new signs—signal shifts in tone. The entry of Pluto into Aquarius, for example, coincides with a renewed focus on technological revolutions, artificial intelligence, and collective movements. The goal is not to predict, but to identify possible turning points—like a cosmic clock ticking beneath history.

Crises, Transformations, and Rebirths

Mundane astrology can shed light on major historical episodes, provided it never falls into the illusion of simple causality. The two World Wars, for example, were preceded by strong planetary concentrations and tense configurations: Saturn–Pluto in 1914, and the Saturn–Uranus conjunction shortly before 1939.

In the 1950s, André Barbault predicted a possible period of détente around 1989–1990, which did in fact coincide with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet bloc. He emphasized the importance of cyclical periodicity, but also stressed that planetary effects must be interpreted within context—not in isolation.

Raymond Merriman, in his work on financial markets, highlighted the relationship between planetary cycles and economic fluctuations. He demonstrated how certain cycles correlate with speculative bubbles, phases of growth, or sharp reversals. The connection is less astrological than statistical—which is precisely what makes his approach so compelling.

Theodor Landscheidt, for his part, attempted a broader modeling, linking planetary cycles, meteorology, and social fluctuations. His work, although unconventional in classical astrology, was already anticipating certain forms of systemic thinking.

The Illusion of Founding Dates

When attempting to draw up an astrological chart for a country, a company, or an event, the first difficulty is often... choosing the right date. For a state, should one use the declaration of independence? The adoption of the constitution? The first military act? Or even, in some cases, international recognition?

Nicholas Campion has compiled over 200 national charts. The goal is not to settle on a single answer, but to compare, cross-reference, and assess the relevance of each chart in light of the events it appears to reflect. This comparative, empirical approach is both the most reasonable—and the most humble.

For companies or corporations, the confusion is even greater: the moment of the idea? The signing of legal documents? The trademark registration? The transfer of capital? The most cautious astrologers agree that one should work with several key dates, and never rely on a single chart as if it were a personal birth chart.

It is in this caution that the rigor of the approach lies. Trying too hard to extract meaning from a single moment leads to tailor-made symbolism—where anything can be retroactively justified.

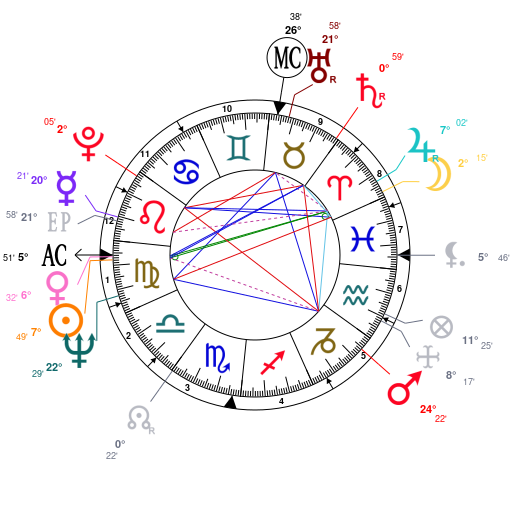

Astrocartography: Beautiful Maps, Little Evidence

Astrocartography, popularized in the 1970s, is based on a seductive idea: projecting the same birth chart onto a world map, aligning planets with key axes (Ascendant, Midheaven, etc.). This is supposed to allow one to locate geographic zones where a given planet exerts greater influence.

In practice, however, the results are often disappointing, contradictory, or anecdotal. Wars do not consistently break out along Mars lines, natural disasters do not reliably follow Pluto, and success does not consistently align with Jupiter. As H.S. Green noted, planetary geography offers no guarantee—celestial maps do not account for geopolitical realities or the historical constructs of nation-states.

Claude Ganeau emphasizes the lack of empirical validation for these global astro-maps. Too many interpretations are made after the fact, by overlaying planetary lines onto past events, without any clear or reproducible predictive value.

It is arguably one of the weakest areas in contemporary astrology: visually appealing, but intellectually fragile.

Since the 1980s, a personalized version of this technique has also flourished: “Where should I vacation?” “Where should I move to find love or career success?” “Which city best supports my artistic potential?”

Although personal astrocartography gained some traction—especially through Jim Lewis himself, and authors like Martin Davis (Astrolocality Astrology)—the actual results are often vague, anecdotal, or retroactively self-validated.

The subjectivity of personal experience, the influence of expectations, and the lack of any serious statistical validation cast considerable doubt on the real reliability of this method.

After more than forty years of use, no independent study has confirmed the effectiveness of these geographic projections in individual lives. At best, the use of astrocartography remains a playful tool.

Conclusion: An Astrology of Cycles, Not of Certainties

Mundane astrology is neither a science nor a divinatory art. It is a tool for symbolic analysis—a way of reflecting on the rhythms of history and the resonances between the heavens and society. It does not explain everything, but it offers a framework for interpreting collective timelines that deserves careful study.

Its strength lies in the study of large planetary cycles, slow-moving configurations, and epochal shifts. There, it touches something profound: the sense that history may at times follow rhythms greater than those of individuals.

But the method begins to falter when one tries to pinpoint events, base analyses on uncertain dates, or draw astrocartographic maps of the world. Caution is needed. Mundane astrology holds great promise—provided we remain clear-eyed about its limits and stay committed to intellectual rigor.

Bibliography

- Barbault, André. Les Astres et l'Histoire. Paris: Éditions Jean-Jacques Pauvert, 1967.

- Barbault, André. L'avenir du monde selon l'astrologie. Paris: Éditions du Félin, 1993.

- Campion, Nicholas. The Book of World Horoscopes. Bournemouth: The Wessex Astrologer, 2004.

- Ganeau, Claude. Astrologie mondiale et événements contemporains. Paris: Éditions Traditionnelles, 1982.

- Green, H.S. Mundane or National Astrology. London: W. Foulsham & Co., 1911.

- Harvey, Charles, Baigent, Michael, and Campion, Nicholas. Mundane Astrology: The Astrology of Nations and Groups. Wellingborough: Aquarian Press, 1984.

- Landscheidt, Theodor. Cosmic Cybernetics: The Foundations of a Modern Astrology. Aalen: Ebertin-Verlag, 1973.

- Meridian, Bill. Planetary Economic Forecasting. Cycles Research, 1994.

- Merriman, Raymond. The Ultimate Book on Stock Market Timing (Vols. 1–5). Farmington Hills: MMA Publications, 1997–2012.

- Tarnas, Richard. Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. New York: Viking Penguin, 2006.

Sign In

Sign In